Rifle Brass Sorting Experiment - Part One

The Correlation Between Weight and Capacity

Weight-sorting brass has become a fairly common practice in the world of competitive rifle marksmen and precision reloaders. Similar to bullet sorting, this operation seems intuitive when the goal is maximizing consistency by minimizing variation.

Those who sort their brass by weight may believe that case weight is directly proportional to case capacity and a shortcut to the tedious process of measuring volume with a liquid. Personally, I haven't seen much evidence to support this belief, so this experiment series will begin by exploring the relationship between case weight and case capacity.

As usual, the raw datasets are available on GitHub.

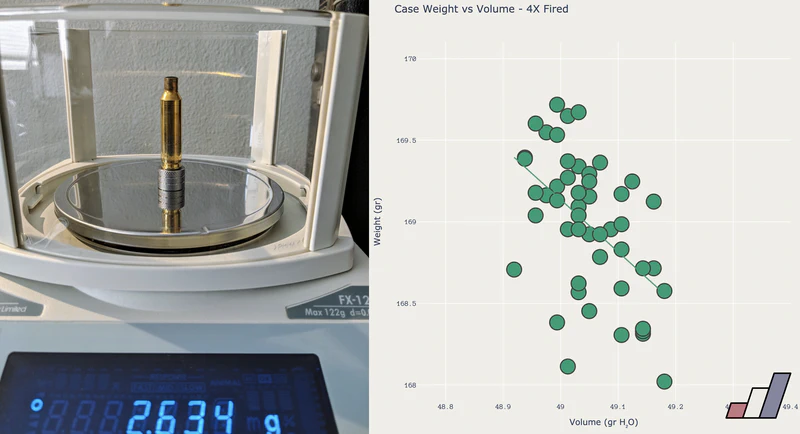

Measuring brass rifle cases by weight and volume.

Table of Contents

Disclaimer

While reading this article, I only ask that you keep an open mind. As I detail my reloading practices and equipment, they will likely differ from your own. Some may be tempted to brush aside my conclusions due to these differences if they feel my methods are not up to their standards. I'm not making claims about the quality of my ammunition or my process. My goal here at Ammolytics, is to explore one variable at a time, measure the impact it has on my load development and on my scores with my rifle, and to share it with you.

Overview

Of the four components that make up a precision rifle cartridge (bullet, brass, powder, primer), only the brass case is designed for easy reuse. Reloaders go to great lengths to extend the service life of their brass, especially when using expensive, high-end brands. After firing, the brass is typically deprimed, cleaned, inspected, measured, annealed, resized, measured, trimmed, and measured again before it's ready for use.

When it comes to rifle brass and its role in creating consistent and precise ammunition, some of the dimensions measured matter more than others. One dimension in particular, case volume, is not only important but also quite annoying to measure, which means people will skip it or take shortcuts. The common method for measuring case volume requires filling a fire-formed case completely with distilled water (without air bubbles) and weighing it. The volume is the measured difference in weight between the empty case and filled. In this experiment, I followed this procedure several times for 50 rifle cases – I can confirm that it's a real pain and error-prone.

QuickLOAD relies on case volume as a critical dimension for its internal ballistics simulations. Volume determines how much powder can fit into the case, the combustion chamber dimensions, and therefore the resulting pressure from ignition.

So, if it's both important and difficult, then there's value in alternative measurement techniques which are reliable, deterministic indicators of case volume.

Open Questions

Here are a few of the questions I hope to answer:

- What is the relationship between case weight and case volume?

- How do case weight & volume change after fire-forming and trimming?

- Does brass sorted by weight or volume correlate to meaningful differences in chamber pressure or muzzle velocity?

- Does brass weight correlate to factors other than volume which might affect pressure and velocity?

- Is there an easier way to measure case volume?

If previous experience has taught me anything, it's that we should expect to find even more interesting questions along the way.

The Correlation Between Case Weight and Volume

A correlation certainly exists between the weight of a brass rifle case and its volume, which can be demonstrated with hypothetical and impractically extreme examples. Consider the following:

Given a pair of rifle casings with identical exterior dimensions, what is the maximum range of weight and volume?

Disregarding safety and usefulness, the range is:

- On the low end, the casing could be a single molecule thick. It would be very light with a large volume.

- On the high end, the casing could be completely solid. It would be very heavy with zero volume.

As I said, neither end of this spectrum is remotely useful, but it demonstrates my point – a correlation between case weight and volume does exist.

More practically, there's a small slice of this spectrum in which actual rifle brass resides. Unfortunately for those of us who wish to sort our brass more easily, it's in this small area where the relationship still exists but is less direct and dramatic, and perhaps less useful.

Why Does It Matter?

This topic matters as much as consistent ammunition matters to you, the reader. After all, don't we all strive to one day see zero variation shot-to-shot on our chronograph from a 10-shot group? As always, I hope to quantify how much this detail matters and to know if sorting by weight is a reasonable stand-in for measuring case capacity, or if it's a waste of time.

The following surveys, simulations, and articles relate to this topic and are worth consideration before moving on to the experiment.

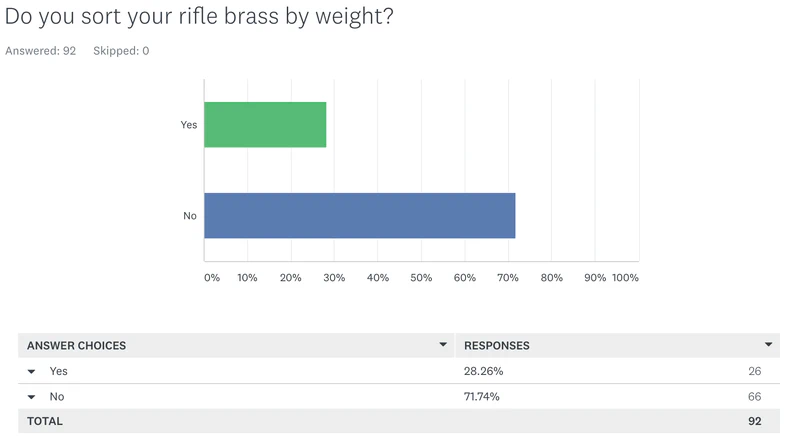

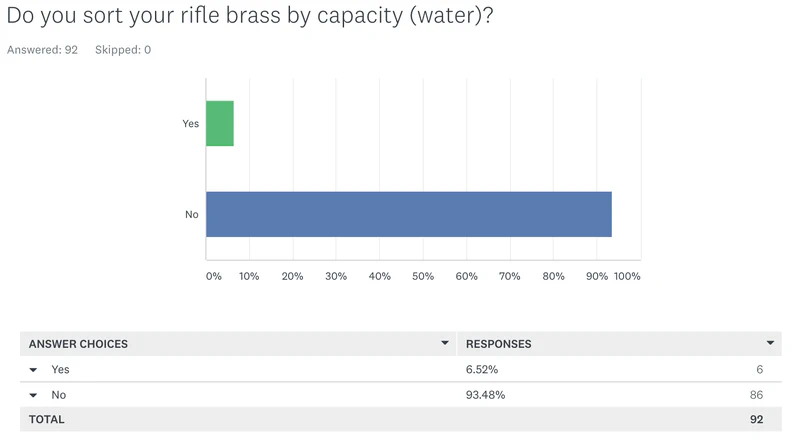

Reader Survey Results

To get a better sense of how much it mattered to my readers, I asked a few questions about brass sorting in a survey. Here are the results.

Survey Results: Do you sort your rifle brass by weight?

Survey Results: Do you sort your rifle brass by capacity?

While this survey may not provide any conclusive results, it does provide some confirmation that sorting rifle brass by weight is fairly common and sorting by volume isn't.

QuickLOAD Simulation

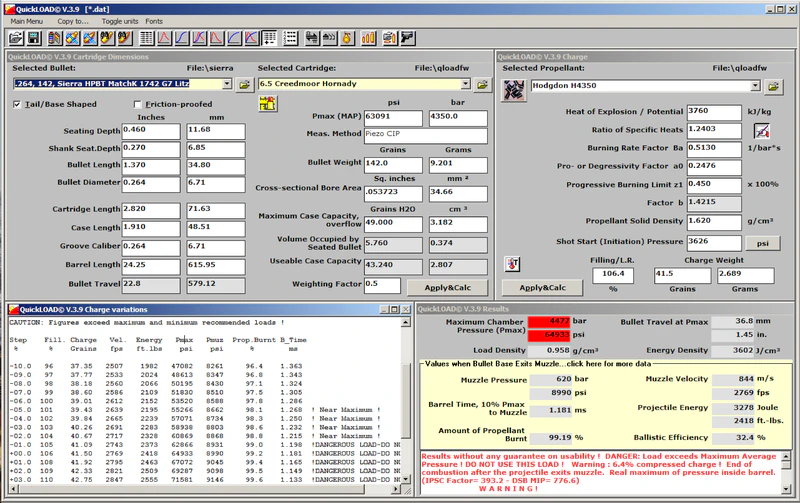

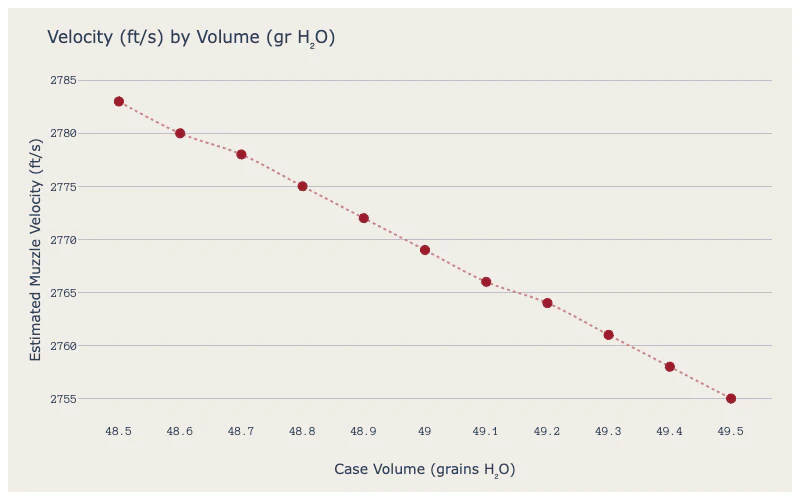

Using my standard 6.5mm Creedmoor load data as a baseline and leaving all other variables the same, I used QuickLOAD to simulate a 1.00 grain (H₂O) difference in case volume and estimate the effects on on muzzle velocity.

Note: QuickLOAD does not have a small rifle primer case for 6.5mm Creedmoor in its library, so the chamber pressures are listed as dangerous. With my rifle, they measure in the normal and safe range with this load.

QuickLOAD: 49.00 grain (H₂O) case volume estimated 2769 ft/s

The following chart shows the muzzle velocity estimated by QuickLOAD for 0.10 grain (H₂O) increments of case volume.

interactive_space Open Interactive Chart

interactive_space Open Interactive Chart

These results show +/- 3 ft/s for every 0.10 grain (H₂O) difference in case volume. If these estimates are correct, then a 0.50 grain (H₂O) case volume variation translates to a significant +/- 14 ft/s muzzle velocity spread.

It still remains to be seen if a 0.10 grain difference in case weight translates to the same difference in case volume and if these predicted changes in velocity match reality.

Precision Rifle Blog

Reloading Like a Pro - Tips From Top Precision Rifle Shooters

Finally, just 12% of the shooters said they weight-sort their brass. You may be surprised to see that number so low, but understand most of these guys are intentional about starting off with good quality brass from the same lot. When you do that, it can dramatically decrease the need to weight-sort brass.

The key takeaway here was that most of the shooters he surveyed didn't sort by weight and instead just bought the best brass they could get to minimize variation.

It's interesting to compare the 12% from his survey with the 28% from mine. Our sample sizes were very similar (100 in his vs 92 in mine), though only 30% of folks in my survey identified as competitive shooters whereas all of his were surveyed at a PRS competition back in 2015.

AMP Annealing

Annealing Under the Microscope, Part 3

Where in the case does the weight variation occur? On this evidence, overall case weight variation was minimal in all packs of Lapua, Peterson and Norma cases. What variation there was did not affect either the AZTEC code generation or annealed hardness. Therefore, any weight variations with those cases must be in the case heads. Brands "A", "B" and "C" showed clear evidence that at least a portion of the case weight variation was in the targeted annealing zone. This may have implications beyond the scope of this study, in particular variable case volume.

This was an incredibly detailed article and in some ways goes far beyond my measuring capabilities. While this study was not focused on case volume, it was interesting to see it mentioned as it related to case weight distribution.

Peterson Cartridge

Weight Sorting – Fact or Fiction

The main variables that cause differences in weight from case to case are as follows:

- Material removed when cutting in the extraction groove.

- External head thickness

- Head diameter

- Sectional density of the webbing (the base of the casing)

Notice what each of these have in common? They don’t relate to internal volume.

As in the AMP Annealing article, they too identified that most weight variation is in the case head. Reading this article lead me to believe that sorting by weight wasn't particularly useful. Despite this, Peterson offers "Select Rifle Brass", which comes sorted from the factory by length and weight. This service will set you back about another $0.20 USD per case, pushing it a bit closer to the price of Lapua.

Takeaways

- Some reloaders are sorting their brass by weight According to the results of my survey and an older one from Precision Rifle Blog.

- Multiple sources agree that most weight variation relates directly to the case head dimensions There's also agreement and research which suggests that quality manufacturers are producing highly consistent brass.

- QuickLOAD simulations suggest that small variations in case volume affect muzzle velocity In the pursuit of consistency, I can understand why reloaders who strive for perfection may sort their brass.

The question now is how to sort and whether case weight translates directly to case volume.

Want to see more articles like this?

The generosity of our supporters keeps this site ad-free. It also affords me the components, equipment, and time needed to conduct these experiments and produce great content for everyone.

Check out my Patreon page to learn more about the benefits of supporting Ammolytics. Your support keeps Ammolytics going!

Conducting the Experiment

My usual approach to a problem like this is to compare the extreme values of a single variable. That's harder to do this time because there are so many other variables that affect brass cases which can't be ignored.

The following questions may help you to better understand the complexity:

- Should the cases be sorted by weight when new and unfired, or after they've been fire-formed, resized, and trimmed?

- Can primer pockets be uniformed before weighing, since they reduce weight but not affect volume?

- Can the case mouths be chamfered and deburred, since they reduce weight but not affect volume?

- Does case trimming (neck turning, neck reaming) affect the muzzle velocity?

- How many times does a case need to be fired until it's fully fire-formed, and how does that affect its volume?

- How does cleaning the cases affect weight & volume?

- How can you keep track of the cases?

I didn't have a large quantity of cases to start with, from which the heaviest and lightest could be used for the experiment. Instead, I wanted to focus on understanding how brass dimensions change over several firings. This could help answer a few questions about the overall experiment and to inform future experiments with larger sample sizes.

With that in mind, I fired 50 pieces of new Peterson 6.5mm Creedmoor SRP brass four times over several months. I maintained the same order of the cases as they came in their original box and took several measurements on each one before resizing, after resizing, and after firing.

Because I was interested to see how the case dimensions would change, I intentionally did not trim until after the third firing & resizing.

To avoid errors due to thermal expansion or equipment sensitivity, I took all measurements from the temperature-stable (68°F) environment of my home office. My spouse continues to not be amused.

Case order goes down and to the right, with case #1 at the top-left.

Everything didn't go as planned. Here are a few of the mistakes I made and problems I ran into:

- After trimming, I messed up the case order I suspect I was picking up two cases at a time from one tray and placing them in different positions in another.

- I was using the wrong tools to fill the cases with liquid This increased my margin of error for volume measurements, and took more time because I spilled more frequently.

- One case mouth was damaged beyond repair While depriming cases the fourth time, I bent one of the case mouths and it could no longer be used.

- I didn't measure muzzle velocity throughout In one instance, I installed my suppressor too loose and it flew downrange with my MagnetoSpeed still attached. No damage, fortunately!

Despite these issues, I'm confident that I collected some solid data and that what I learned from my experiment, and my failures, will be useful for myself and others.

Case Measurement and Preparation Procedure

Because I kept the cases in the same order, I could not use the wet tumbling method with stainless steel pins that I normally opt for – instead I used the plastic box the brass came in with an ultrasonic cleaner.

Ultrasonic cleaning brass cases while maintaining the order.

- Deprime

- Clean

- Measure dimensions, weight, and case volume

- Anneal

- Resize

- Trim (only after the 3rd firing)

- Measure dimensions

- Load

- Fire

Case Trimming Procedure

I performed the following steps to trim the brass.

- Flash hole For uniformity only, there was no burr to remove

- Primer pocket

- Length

- Chamfer/deburr

As I mentioned earlier, I intentionally did not trim the brass until after the third firing. I wanted to get a better sense of which dimensions would change after several firings and how long it would take to fully fire-form the cases. Since trimming the length of the case would directly affect case weight and volume, I wanted to avoid that influence until I was confident the brass was fully formed.

A Quick Word About Measuring Volume By Weight

Volumetric measurements are normally represented in milliliters (ml) or US fluid ounces (fl oz). Case volume, however, is often represented in grains of water (gr H₂O), which is a unit of weight. It's measured with a scale instead of a graduated cylinder.

What gives?

The answer is that the metric system's unit of volume and weight of distilled water are directly related. One gram of distilled water equals one milliliter of distilled water. This allows for a very simple conversion from weight to volume, which can be translated to other units of weight, such as grains.

Science is awesome.

Dimensions

Before and after every firing and resizing, I measured the following:

- Shoulder length (in)

- Case length (in)

- Neck diameter (in)

- Neck thickness (in)

After the third firing, I started to wonder about the thickness of the case head, so I began to also measure the following:

- Case depth (in)

- Flash hole depth (in)

Equipment

- Mitutoyo 8 Inch Digital Calipers

- Hornady Lock-n-Load Comparator Body

- Hornady Lock-n-Load Headspace Gauges For measuring shoulder length

- Gage Pins (0.2630" Class Z) For measuring case depth

- Neodymium magnet For measuring flash hole depth

Weight

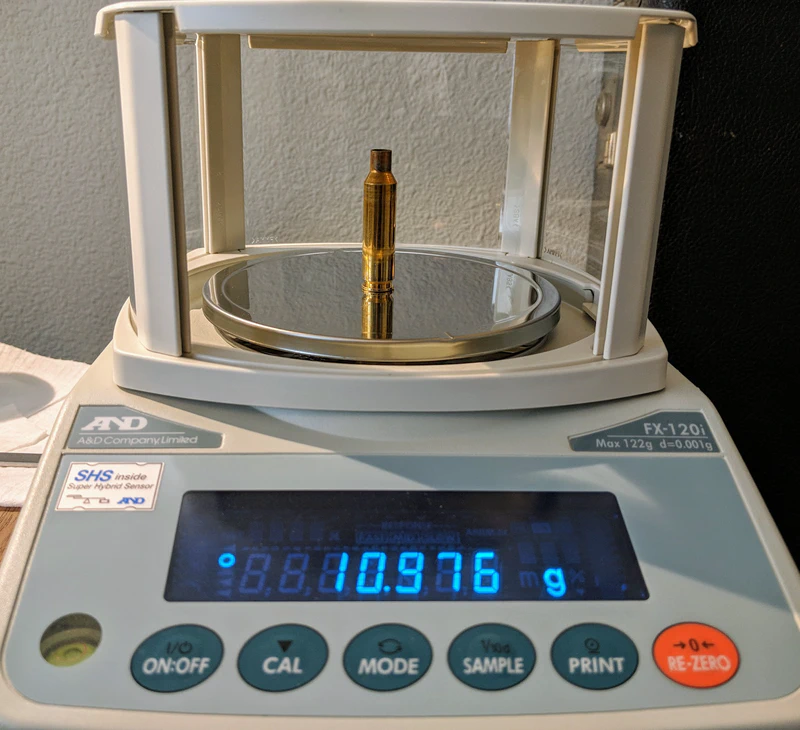

As you might expect, measuring the weight of the cases was pretty straightforward. To increase precision, I measured in grams and converted to grains myself.

Weighing a clean, empty brass case.

Equipment

Volume

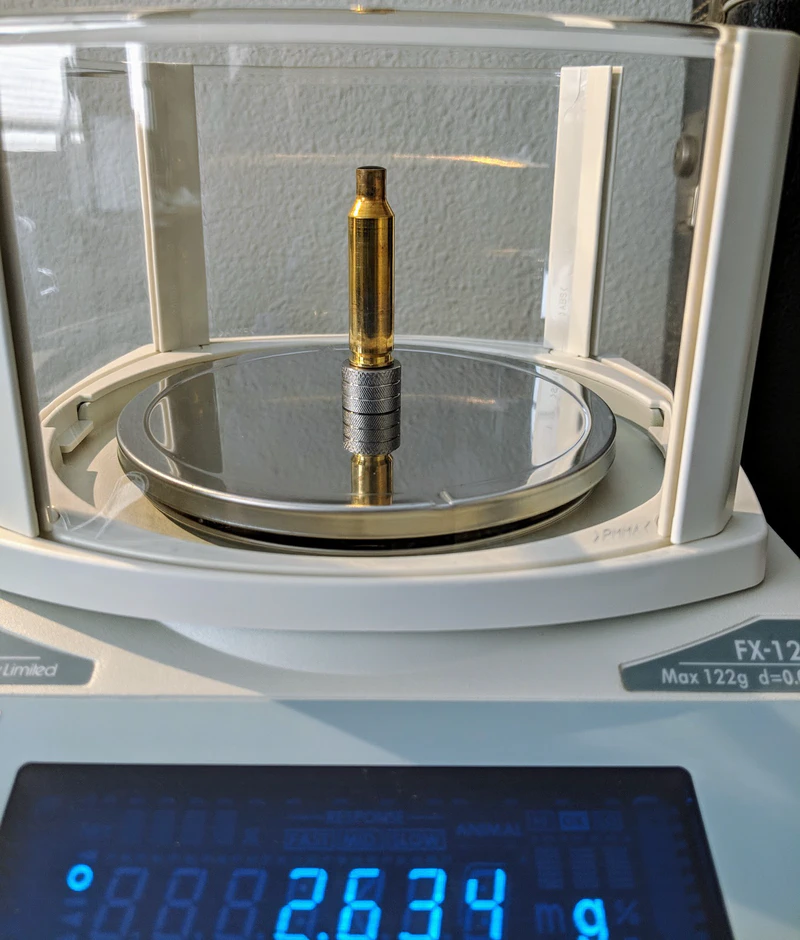

Measuring case volume with 99.9% isopropyl alcohol, an A&D scale, and primer pocket plugs.

Volume was measured with 99.9% isopropyl alcohol after the first, third, and fourth firing, before resizing.

Isopropyl alcohol (99.9%) was used because it has a number of benefits over distilled water.

- Does not produce microbubbles which can stick to the inside of the case, leading to false readings

- Comes very pure from the factory in small, sealed containers

- Evaporates quickly, making it easier to clean up spills and dry cases

The following formula converts the weight of 99.9% alcohol (\(W_{\text{IPA}}\)) to that of distilled water (\(W_{\text{H$_{2}$O}}\)).

$$ W_{\text{H$_{2}$O}} = W_{\text{IPA}} + ((W_{\text{IPA}} \times 0.212) \times 0.999) $$Measuring case volume took the most time. Preventing and controlling spillover while filling to the exact same level was exceptionally challenging. I tried several different tools, and none of them worked particularly well. Only recently, after I already completed this work, have I purchased transfer pipettes and micropipettes, which should significantly ease the process for future measurements.

Equipment

- 21st Century Shooting Primer Pocket Plugs

- A&D FX-120i Scale

- 99.9% Isopropyl Alcohol

- Wash Bottle to fill most of the alcohol into the case

- Irrigation Syringe to add the last few drops

Because isopropyl alcohol is hygroscopic, I only used freshly-opened containers and kept them closed as much as possible. After measuring a case, I drained the used alcohol into a separate container which I considered "contaminated".

Things I Didn't Do

- Measure the volume of unfired brass All references I could find said it would be meaningless, but it may still have been interesting

- Weigh the brass after the second firing No change expected, but may have been nice for consistency

- Measure the volume after the second firing In hindsight, I wish I had done this to monitor the progression

Examining the Results

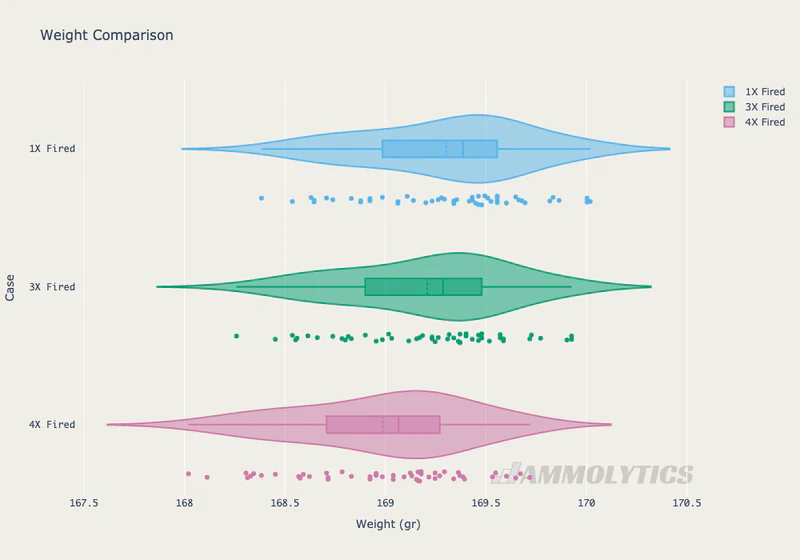

The following table compares the cumulative statistics of the case weight and volume between the first and fourth firing. Remember that the brass was trimmed after the third firing, which explains the shift in average weight.

| Volume (gr H₂O) | Weight (gr) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std Dev | Range | Mean | Std Dev | Range | |

| 1x Fired | 49.14 | 0.13 | 0.56 | 169.30 | 0.41 | 1.64 |

| 4x Fired | 49.05 | 0.07 | 0.26 | 168.99 | 0.43 | 1.70 |

| Change | -0.09 | -0.06 | -0.30 | -0.31 | +0.02 | +0.06 |

Three things stand out:

- The case volume range and standard deviation were cut in half

- The mean weight shifted over 3X as much as the mean volume

- The volume range shifted 5X as much as the weight range

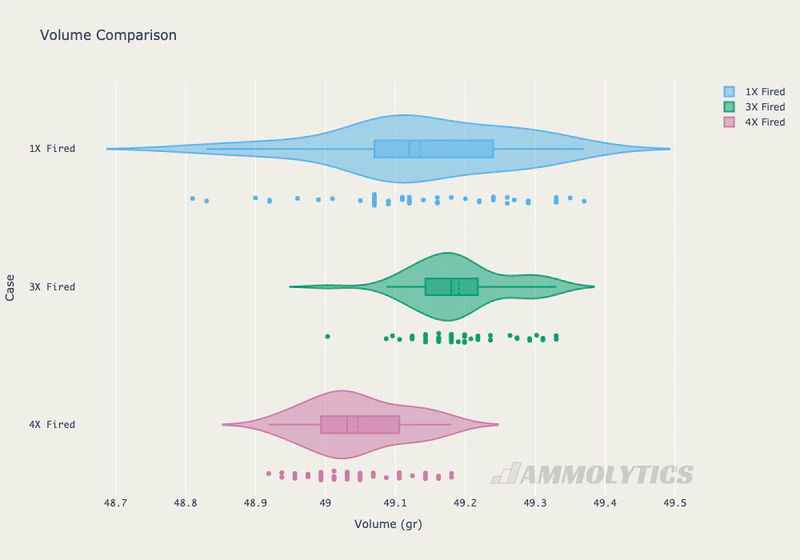

It's not evident in this table, but the consistency gains in case volume happened before the cases were trimmed. This change is more obvious in the volume comparison chart below.

interactive_space Open Interactive Chart

interactive_space Open Interactive Chart

interactive_space Open Interactive Chart

interactive_space Open Interactive Chart

What I notice in the charts above is that the consistency of case weight barely changes while the case volume shifts much more dramatically. A linear regression may provide more insight.

Linear Regression Analysis

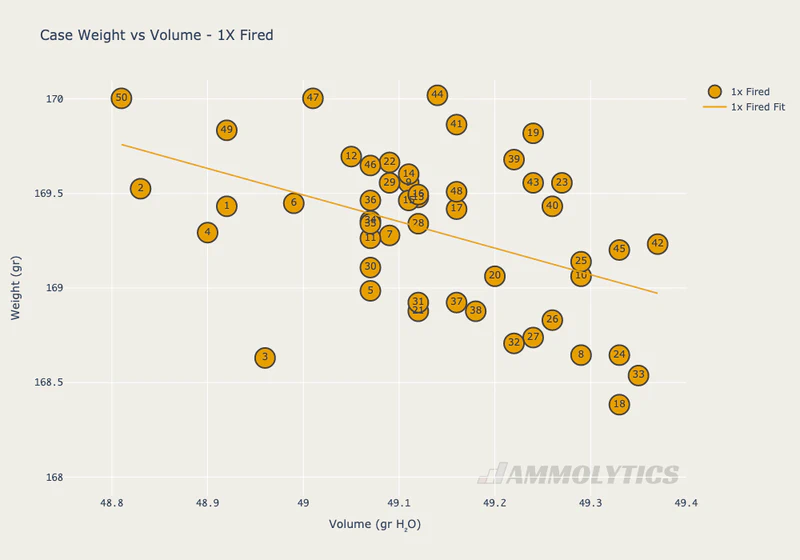

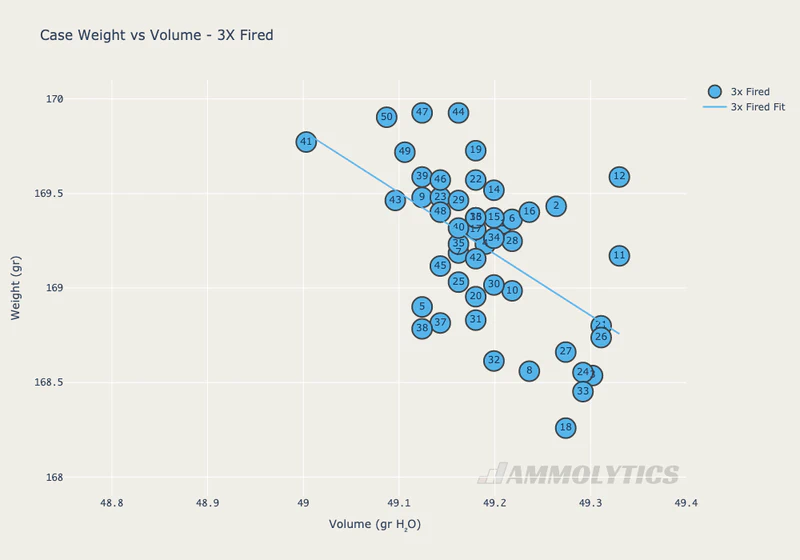

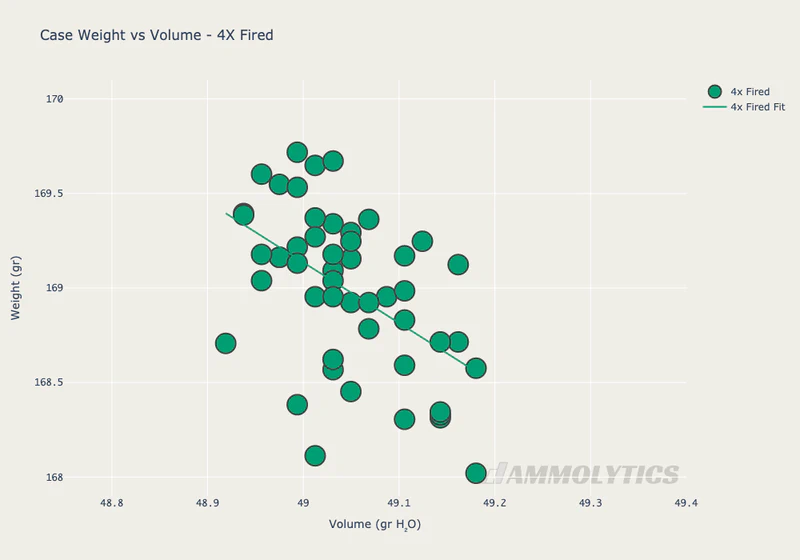

The goal of the following charts is to help visualize the correlation between the volumes and weights of the cases used after three stages of firings. The closer the scatter plots are to the fit line, the stronger the correlation.

It cannot be overstated that these charts do not imply causation.

screen_rotation The following charts are designed for a wider screen. If you're on mobile, try landscape mode.

interactive_space Open Interactive Chart

interactive_space Open Interactive Chart

Things look fairly normal after the first firing. The volume has plenty of variation, even among the same weight.

interactive_space Open Interactive Chart

interactive_space Open Interactive Chart

The case volumes really tighten up after the third firing. Remember, the cases have not yet been trimmed. A majority of cases have a volume within 0.1 gr H₂O of the 42.18 gr mark.

interactive_space Open Interactive Chart

interactive_space Open Interactive Chart

Note: The case number labels were omitted from this chart since the order was lost after the third firing.

The case volume shows slightly less variation after the fourth firing, but this is more likely due to the margin of error in my measurements. As should be expected, the overall weights shifted downward from the material that was trimmed. Personally, I expected there to be less variation in weight at this point – this data does not indicate that, however.

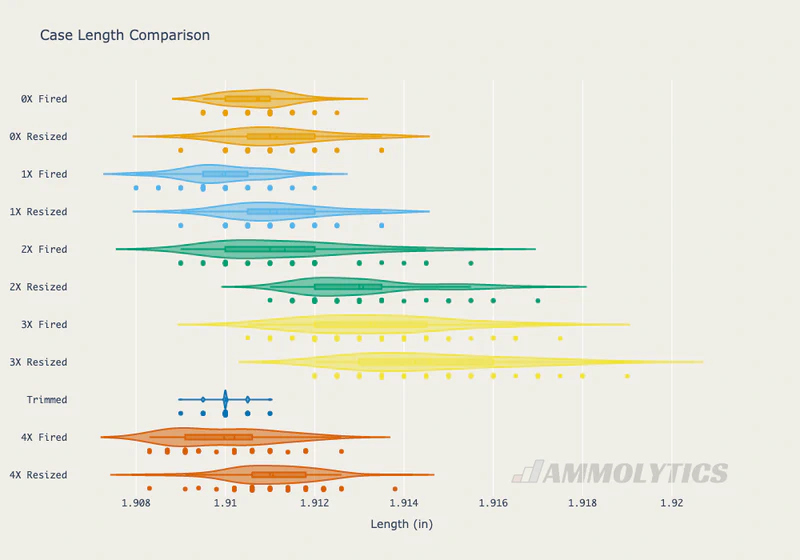

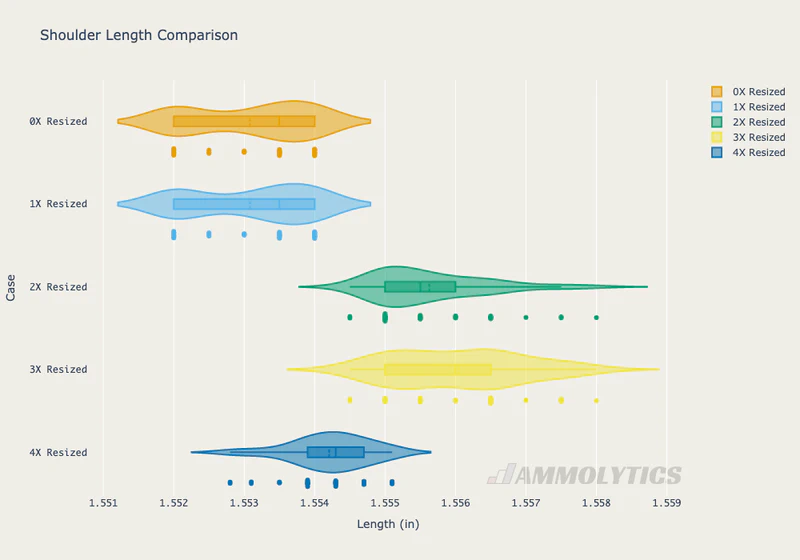

Case Length and Shoulder Length Progression

The following charts are more interesting than they are experimentally useful or conclusive, but I thought I'd share them anyway since they still taught me something interesting about my reloading method.

interactive_space Open Interactive Chart

interactive_space Open Interactive Chart

interactive_space Open Interactive Chart

interactive_space Open Interactive Chart

What these charts made me realize is that I had set up my resizing die to bump the shoulder back based on a once-fired case. Clearly, the brass had not yet been fully fire-formed, which means that I've been resizing my brass more than I need to.

Conclusions

Here's what I've learned and can conclude based on the evidence from this first brass sorting experiment.

- Small variations in case volume may affect muzzle velocity The measured volumetric difference in my cases was 0.26 gr H₂O after the fourth firing, which QuickLOAD suggests an 8 ft/s velocity spread as a result.

- Sorting by case weight will not guarantee consistent case volumes More data is needed to confirm this, but I did not see evidence of a strong correlation in this experiment.

- Fire-formed and trimmed brass improves the case volume variation, but not the weight variation A rather surprising finding which matches what others have said – most weight variation is in the case head, not wall thickness.

- Brass isn't fully fire-formed on the first firing Two firings were required to fully fire-form this brass (but three is better). Remember this when setting your resizing die to bump the shoulder back.

Next Steps

This is just the first in a series of brass sorting experiments, which I'll continue to explore. Be sure to subscribe to the mailing list below or follow on your social media platform of choice to be notified when the next one comes out.

- Collect more data, different brands of brass Using what I've learned in Part One, I'll continue this experiment with 100 cases each of three different brands (Lapua, Peterson, Hornady).

- Collect muzzle velocity and chamber pressure data This will help to verify the accuracy of QuickLOAD's simulation, and to prove how meaningful case volume is.

- More dimensional measurements I have some ideas about measuring the case head dimensions, which may allow it to be factored out of the weight. If this is possible, it may allow for weight sorting cases to be more meaningful.

- Continue firing these cases I'm curious to learn if the case length continue to change. Perhaps we just trim once?

- Don't just take my word for it! Try this experiment for yourself to see if you can reproduce the same results. If you do, please share your work with me so that we can all learn together!

- Have questions or feedback? You can discuss this project with me on Reddit.

- Contribute Ammolytics is a community-supported project to keep it free of ads and paid-promotions. Making purchases using the affiliate links on this site helps to fund future projects and experiments. You can also support Ammolytics on Patreon!

Special thanks

- To Rick Burton and the rest of my Patrons, for their continued support which allows me to do this work.

- To my wife, for her incredible patience and support.

Before you go…

Thanks for taking the time to read this article! I enjoyed writing it and learned a lot in this process and I hope that you did too. If you have any feedback, you can email me directly if you don't prefer to use Reddit or other social media.